Journalology #137a: Rupture

Hello fellow journalologists,

Some weeks it’s hard to write this newsletter, not because of lack of material but because academic publishing seems so trivial and unimportant compared with wider global events. This was one of those weeks. For the first time I sense, as a European, a rupture between my continent and at least some of North America. And that makes me very, very sad.

The bright spot of what was a dark, difficult week was undoubtedly Mark Carney’s speech at Davos, which provided both hope and light. The Canadian prime minister (and former Governor of the Bank of England) showed that statesmanship with a backbone is possible in 2026.

This newsletter is about academic journals, not global politics, but hopefully you’ll indulge me as I reuse some of Prime Minister Carney’s words to fit the topics covered by Journalology. The quotes that follow are all from his Davos speech; the scholarly publishing community can learn lessons from his courageous words.

Carney kicked off with an anecdote from Czech dissident Václav Havel’s essay The Power of the Powerless, which explored why communism was tolerated by ordinary people. Carney told the story as follows:

Every morning, this shopkeeper places a sign in his window: ‘Workers of the world unite’. He doesn’t believe it, no-one does, but he places a sign anyway to avoid trouble, to signal compliance, to get along. And because every shopkeeper on every street does the same, the system persists – not through violence alone, but through the participation of ordinary people in rituals they privately know to be false.

In my experience, the vast majority of publishing professionals, commercial and not-for-profit alike, are deeply committed to the core principles of academic research. However, at a point in time when quantity seems to matter more than quality — both within academia and within publishing — perhaps we should look ourselves in the mirror and ask whether we’re taking part in “rituals that privately we know to be false”.

Small and medium-sized publishers are struggling to compete in an environment where scale wins; research integrity challenges, transformative agreements and AI all require significant financial investment. Medium-sized publishers talk a lot about collaboration, but actions speak louder than words. Or as Carney put it:

… the middle powers must act together, because if we’re not at the table, we’re on the menu.

The research-integrity challenges that we collectively face have the potential to bring out the best in us. The STM meeting on research integrity in London last December gave me hope; there was a real sense of collaboration and collegiality, of a willingness to tackle hard problems together. In Carney’s words:

Collective investments in resilience are cheaper than everyone building their own fortresses. Shared standards reduce fragmentations. Complementarities are positive sum.

Many publishers are in denial about the shift in the balance of scientific power, from the west to east. As a reminder, China published twice as many research papers as the USA last year, hitting the 1 million article mark for the first time (the 2025 article numbers in the below graph will get larger as more 2025 content is added to the Dimensions database over the next 6 months).

The coming decades in academic publishing will be defined by China, which is building its own publishing infrastructure, and yet at the recent APE meeting in Berlin China barely got mentioned. The future will look different from the past. We need to think like Carney:

So we’re engaging broadly, strategically, with open eyes. We actively take on the world as it is, not wait around for the world we wish to be.”

Speech writers and editorialists often finish off an argument by referring back to something mentioned at the start of their monologue. Prime Minister Carney’s bottom line at Davos circles back to Václav Havel’s anecdote about the shopkeeper in Czechoslovakia; Carney makes the point that the illusion of the rules-based order, which superpowers break whenever it suits them, has been dispelled. His speech at Davos may be remembered as one of the defining moments in 21st century geopolitics.

We are taking the sign out of the window. We know the old order is not coming back. We shouldn’t mourn it. Nostalgia is not a strategy, but we believe that from the fracture, we can build something bigger, better, stronger, more just. This is the task of the middle powers, the countries that have the most to lose from a world of fortresses and most to gain from genuine cooperation.

Scholarly publishing, for all its faults, bears only a passing resemblance to the seismic shifts occurring on the global political stage. Yes, the large commercial publishers sometimes build fortresses and accumulate power in the form of increased market share; that’s a feature of their ability to attract capital investment. But they are also often the leaders of the “rules based order”, creating, and investing in, core infrastructure like Crossref and initiatives like United2Act.

We should observe what’s happening in global politics and reject unilateralism. Small and medium-sized publishers, which serve niche audiences, have a place at the academic top table; they need to collaborate, not compete, to ensure they stay off the menu.

Research is a global enterprise, driven by human beings’ innate desire to understand the universe and our place in it. Shared standards reduce fragmentations. Complementarities are positive sum. Together, we can build something bigger, better, stronger, more just.

News headlines

The rise of China’s research: a global opportunity

The next decade will unfold in a multipolar and increasingly complex scientific landscape, where rivalry and collaboration coexist. Yet the history is clear: the best science often emerges from international collaboration, which depends on data transparency, research integrity, and reciprocity. Although scientific collaborations between the USA and China have declined since 2019, those with countries in the Asia-Pacific region, Africa, and the Middle East have expanded rapidly, while its research links with the European Union are strengthening. Although abundant opportunities for international collaboration persist, many are at risk of being missed—data security and geopolitical tensions breed mistrust as well as creating practical barriers to cooperation. China’s ascent as a global leader in research offers a vital opportunity.

JB: Some editors and publishers may be in denial about China, but The Lancet is not one of them, as this editorial illustrates. I often use The Lancet’s development in China as a case study when I give talks. The journal started proactively engaging with China in the early 2000s and in 2008 published a special issue on China and Global Health.

The Lancet’s editors played the long game, betting that China would become a global research powerhouse, perhaps one day overtaking the east coast of the USA, whose universities’ faculty preferred to publish in The New England Journal of Medicine or JAMA. When the pandemic hit, some of the most clinically important papers from China were sent to The Lancet, which built a reputation for championing global health, rather than to its US rivals.

More than half of authors of leading research say funding is declining

Funding for leading research projects around the globe is more likely to be falling than increasing, according to a survey of thousands of researchers who have published some of the most influential science in the past few years. The Research Leaders survey polled more than 6,000 authors of articles published in journals tracked by Nature Index journals since 2020. It found that 53% think funding for leading projects in their field is decreasing; by contrast, 21% say it is rising.

JB: Simon Marginson, a higher-education researcher at the University of Bristol, UK, is quoted throughout the piece, including this:

“The gravity has been shifting to Asia in terms of science funding and higher-education participation for the past 20 years,” Marginson adds, with this now being accompanied by “a strange American implosion, which has accelerated the change in narrative”.

The Impact of Shadow Scholars on Academic Integrity Today

It is estimated that tens of millions of students have benefited from essays written by ghost writers or ‘shadow scholars,’ many of whom live in Kenya as highly educated but underemployed workers. The real crime, as Kingori sees it, is not just the cheating that is going on, but that those who cheat will go on to be doctors, lawyers, or even academics themselves in the future, profiting from well-paid Global North jobs on the back of the work done by Kenyan and other Global South ghost writers. Furthermore, far from being ashamed of their work, many Kenyan writers in the documentary are proud of the work they have done on behalf of others, even though their identity as authors has not been recognized.

JB: The trailer for this documentary is shown below. The full-length film, which launched a few months ago, is available on a number of streaming services.

According to Simon Linacre:

The film is a heartbreaking watch, particularly as there is an even darker threat behind the story, namely the emergence of Generative AI, which threatens the livelihoods of so many ghostwriters almost overnight. While this may remove the injustice of using essay mill workers to further the ends of those who are willing to pay to cheat, it will not remove the cheating itself, which is simply moving to the cheaper, quicker, and more accessible Gen AI platforms.

Science is drowning in AI slop

Now, somewhat ironically, the problem is affecting AI research itself. It’s easy to see why: The job market for people who can credibly claim to have published original research in machine learning or robotics is as strong, if not stronger, than the one for cancer biologists. There’s also a fraud template for AI researchers: All they have to do is claim to have run a machine-learning algorithm on some kind of data, and say that it produced an interesting outcome. Again, so long as the outcome isn’t too interesting, few people, if any, will bother to vet it.

JB: This news feature from The Atlantic is balanced and well written. The article finishes with this paragraph:

When I called A. J. Boston, a professor at Murray State University who has written about this issue, he asked me if I’d heard of the dead-internet conspiracy theory. Its adherents believe that on social media and in other online spaces, only a few real people create posts, comments, and images. The rest are generated and amplified by competing networks of bots. Boston said that in the worst-case scenario, the scientific literature might come to look something like that. AIs would write most papers, and review most of them, too. This empty back-and-forth would be used to train newer AI models. Fraudulent images and phantom citations would embed themselves deeper and deeper in our systems of knowledge. They’d become a permanent epistemological pollution that could never be filtered out.

I’ve probably linked to this before, but my favourite Nature ‘Futures’ article of all time covers a similar topic: A brief history of death switches. If you haven’t read it before, you should. It’s a brilliant piece of writing. This is the basic premise:

With a death switch, the computer prompts you for your password once a week to make sure you are still alive. When you don’t enter your password for some period of time, the computer deduces you are dead, and your passwords are automatically e-mailed to the second-in-command. Individuals began to use death switches to reveal Swiss bank account numbers to their heirs, to get the last word in an argument, and to confess secrets that were unspeakable during a lifetime.

And finally…

The eagle-eyed editors among you will have noticed that the title of this newsletter is “Journalology #137a: Rupture”. Part B of this week’s edition of Journalology will hit paid subscribers’ inboxes around the middle of next week; it will cover all the scholarly publishing news and comment from the past 7 days, together with some analysis and interpretation from me.

I chose to write this week’s newsletter in two halves partly to keep the newsletter’s length manageable, but mostly because I’m going away this weekend and I haven’t finished writing Part B yet...

Until next time,

James

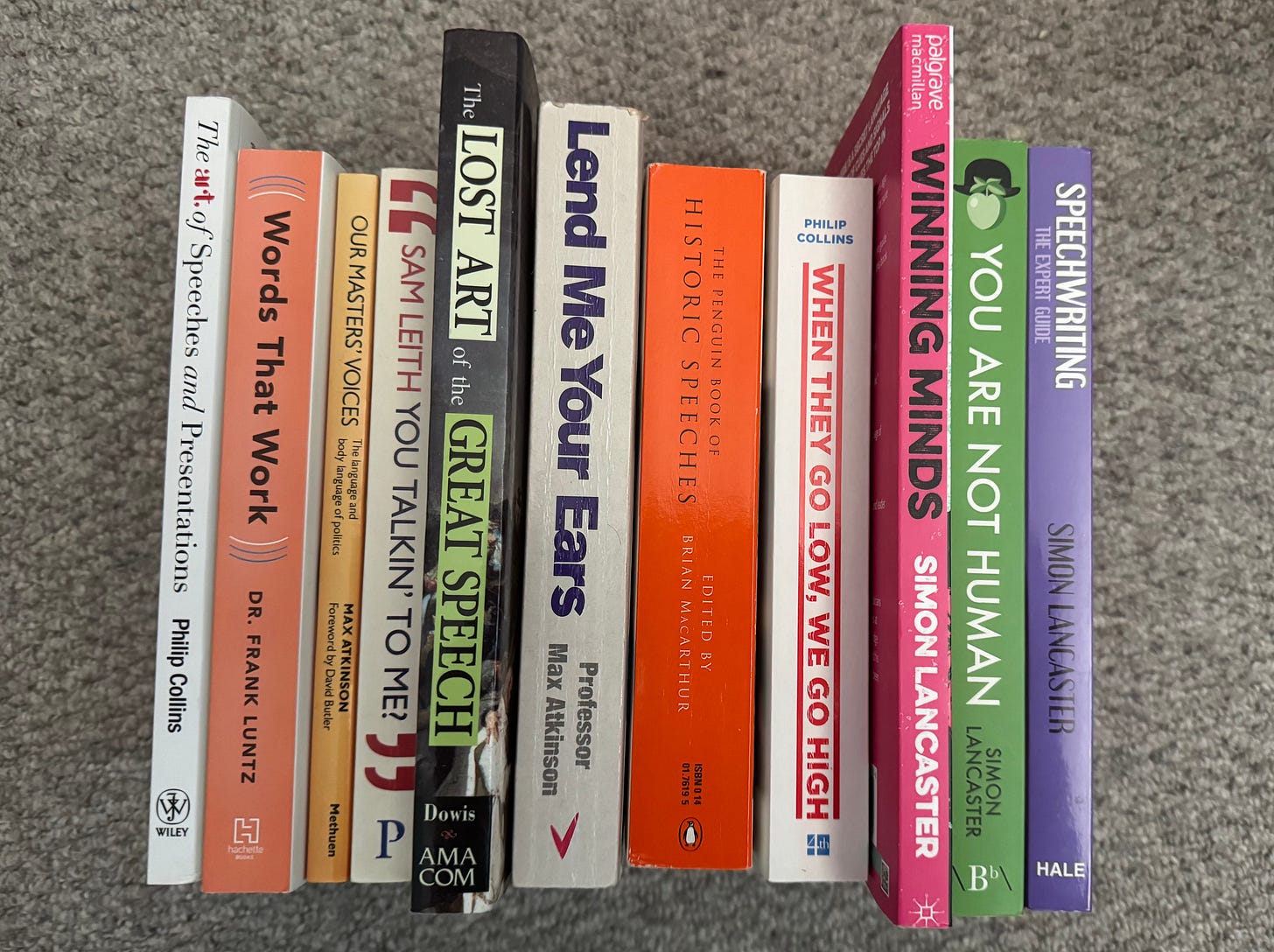

P.S. If you write editorials for your journal I highly recommend dipping into these books. The tactics that speech writers use are directly applicable to writing editorials. Simon Lancaster’s books are my personal favourites.

Everyone should read You Are Not Human: How Words Kill to fully understand the power of metaphor and why the words we choose matter. To give you a taste, watch this video which Simon posted on LinkedIn a few days ago. Powerful stuff.